Although William Aiken Starrett had gone to the seminary and become a minister, I think deep inside, he had really wanted to be an architect like his father. As a kid in Pennsylvania, he’d follow his dad to work, and liked to tag along with the surveyors. When he was ten, his father bought some land outside of Pittsburgh, and sent William with the surveyors to carry their chain. William’s keen instincts caught an error—an error that was confirmed by a second survey. His knack for this kind of stuff was obvious from the start. Also like his father, William was a deep thinker with an artistically creative mind.

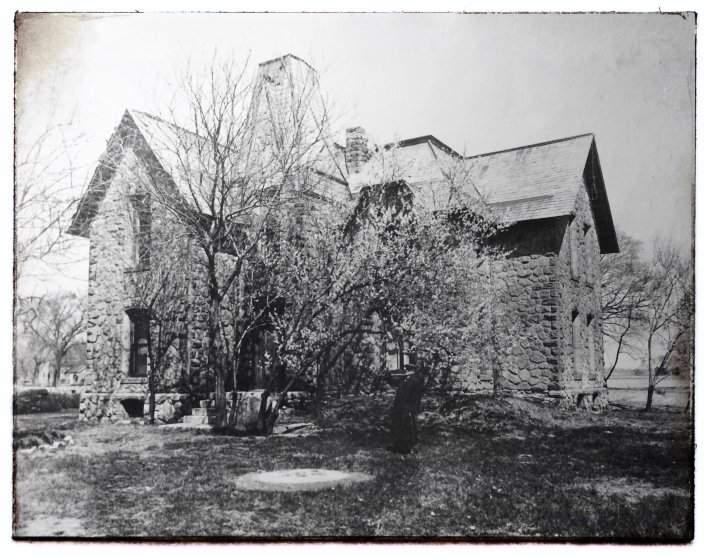

So when he and Helen were ready, he seized the opportunity to design and build his bride their dream house. I’ve heard that Dr Ekin bought the newlyweds their 20-acre farm in North Lawrence, but I can’t locate records to confirm or deny it. Regardless, the couple acquired a beautiful piece of property in the newly available territory north of the Kansas River. The land had rich, fertile soil, and a grove of walnut trees that promised shade in the summer, a windbreak in the winter, and a plentiful annual nut harvest. William drew up the plans and set to work. He included everything he wanted.

The 14 room, two story house had large windows on every wall to let in sunlight and fresh air—and allow the family breathtaking vistas of the sweeping Kansas prairie, where, on occasion, the last of the American Indians could be seen walking along their ancient trails, disappearing into the west.. The steeply pitched roof was tiled with fire-proof slate, and copper guttering provided adequate drainage. He even included a full basement with a root cellar. Every inch of the home reflected his own personal style with many advanced features. The walls were built from native Kansas sandstone mined from nearby Mud Creek and hauled in by wagon. Using an old masons’ technique he’d learned from his father, each of the irregular, hand chiseled stones was catalogued, charted, and numbered before being put into place. As the pastor of the Presbyterian Church, it’s likely that he had the help of his parishioners and friends in the actual construction.

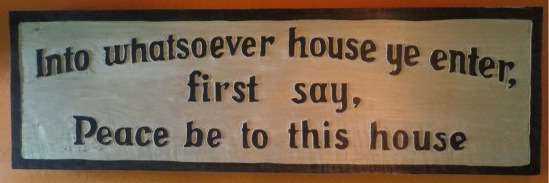

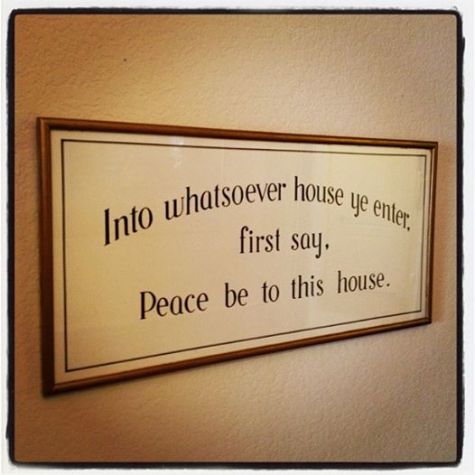

The home’s entryway was warm and welcoming. William harvested walnut timber from the grove and beautifully carved an intricate design into the thick, hearty wood. And above the door was a transom in which he would hang a window etched with words that would remain in the family for generations, though many of his descendants wouldn’t know where they first appeared until more than 150 years later. The consummate artist, William warmed some beeswax and carefully spread it on a piece of glass. With a knife, he cut into the wax, in simple, hand-cut lettering, the motto of his household and one of his favorite bible verses:

William and Helen turned the sandstone, slate, and walnut building into a warm and inviting home. Together they welcomed seven children into their family—all of them born in the house. Money was tight, so they were always busy. Yet, the family was consequently quite happy. The kids spent the warm months barefoot, working the farm, harvesting vegetables, caring for the animals, and exploring the landscape of the area. They often ignored their parents’ orders and swam in the Kansas River when it was low, searching for softshell crabs. Evenings were spent gathered in the parlor as William shared his love of Shakespeare with his children.

Education was never an afterthought in the Starrett household. With two parents who were trained teachers, the children received a thorough education. William allowed more leniency into the artistic arena, but Helen made sure the children were properly educated in the necessary subjects. Other than William, Helen, and the children, other family members would live in the home for varying periods of time. William’s mother, Ellen, came to live with the family until her death in 1877. William’s sister, Annie Starrett, lived with them, as did Helen’s sister Annie Ekin. Helen’s parents and sisters also came frequently for extended visits.

The home played a role in the American Women’s Suffrage Movement as well. During 1867, Susan B Anthony stayed with the Starretts for more than six weeks during her campaign across the country. Suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Rev Olympia Brown met with Miss Anthony and Mrs Starrett in the parlor, and when Miss Anthony announced her intention to campaign for a Constitutional Amendment, the document was drawn up in the Starrett home in Lawrence.

Helen Ekin Starrett became a delegate from Kansas to the National Suffrage Convention and would gain fame from her participation in the movement. Kansas Governor Charles Robinson was a frequent guest in the home, as were other friends like Henry Ward Beecher, John Fraser, and other founders and fellow regents of the University of Kansas.

The Starrett family relocated to a suburb of Chicago in January of 1880. In a Lawrence Daily Journal story detailing their departure and status of the property the house is referred to as the “Starrett Mansion,” and optimistically states that it would be offered for rent beginning at the end of January 1880 if a buyer wasn’t found sooner. Until 1883, the Starrett place in North Lawrence wasn’t mentioned in any of the Lawrence papers, so I assume that the Starretts had regular renters, but the house remained for sale.

Beginning in 1883, the property began to make regular appearances in the news, beginning with a story with the headline “North Lawrence Muddle” that the Board of Health “decided to take over the house,” evict its occupants, and use the property as a quarantine hospital for smallpox patients. The marshall was called to forcibly remove the families. A judge blocked the Board from removing the renters and placed the property in the hands of the Douglas Country Sheriff. Within days, a lawsuit was filed by the tenants, but it did little good. By the end of the year, the place had been listed as delinquent on its property taxes, and would be offered up for auction by the Douglas County Sheriff.

For the next three years, various Lawrence newspapers reported on William’s travels in and out of town on legal business. As William was a lawyer, if you weren’t aware of the tax problems on the house and the farm, or the Starretts’ pending bankruptcy filing in the state of Kanses, his legal business doesn’t sound ominous. However, as I was aware of the issues swirling around him at the time, this must have been heartbreakingly difficult for him. On January 8, 1887, his business travels abruptly stopped.

In my research over the years, I’ve read a lot of death notices, but few with such strong undertones of sadness as the notice informing the people of Lawrence, Kansas that William Aiken Starrett had passed away in Chicago after a short bout with typhoid pneumonia at the age of 52. It spoke of his profound influence on the people of Lawrence and his impact on the frontier community’s foundation. Additionally, it made note of the “cloud of his latter years in this place,” an obvious foreshadowing to the public auction notice of the Starrett property that would be printed just three months later.

Shortly after his death notice was printed the farmland was turned to pasture. But the property didn’t sell. In the meantime, it continued to play host to a range of different outdoor social events.

Tracing its journey wasn’t easy because of the various names used. “Starrett Grove,” “Walnut Grove,” “the Starrett Place,” “Starrett’s Park,” “Walnut Park,” and “the Starrett Property,” and even “the Castle,” were the most frequently used names. Church picnics and tent revivals seemed to be the most common events advertised. And something I learned here—a 19th Century tent revival in frontier Kansas was no small affair. These things lasted for weeks at a time. Families traveled a great distance and camped out. Apparently, these things were HUGE.

In 1888, the property changed hands, and a year later, the land was surveyed and it was reported that after some pieces had been sold off, 18-acres still remained intact. Sewer services were added and a road was put in to provide better access. Community picnics, Church functions, and tent revivals remained the main draw to the property, and in 1892, the AME Church sponsored a huge 4th of July BBQ picnic and invited the whole town. The affair was hailed as a huge success—and received one of the craziest write-ups I’ve ever read. (This deserves a post all its own! Coming soon!)

Towards the end of 1892, Dr Walter Seward Bunn purchased “the Old Starrett Castle,” and announced plans to remodel and refit the house as a private hospital with a modern operating room and would have capacity for 25 patients and an apartment for the Bunn family. They held an open house for friends, and invited all interested to come see the new “Walnut Park Rest.” I’ve also seen it called “Walnut Grove Hospital” and “Dr Bunn’s hospital.” (It’s really frustrating how inconsistent names and spellings were back then! It makes researching a very time consuming undertaking.) After the open house, the Lawrence Daily Journal ran a story detailing the new facility and its many features. The final sentence of the story brought a tear to my eye, and as I read it, the tear trickled town my face.

It is interesting to see that the transom window over the front door, placed there when the house was first built, has been preserved unbroken, during all these years of careless occupancy. It bears a text in the glass, which was put there by the builder, Rev. Mr. Starritt (sic) of the Presbyterian church of this city. A more fitting verse could hardly be found, considering the present use of the house, “Into whatsoever house ye enter, first say, ‘Peace be unto (sic) this house.’”

For the next few years, Dr Bunn and his wife ran the Walnut Grove Hospital in North Lawrence. The doctor answered calls at all hours, performed lifesaving surgeries, and treated all patients– regardless of ability to pay– and never turned a case away. During the diptheria epidemic, he treated its victims, and eventually brought the disease to his entire family. The Bunn family was placed under quarantine in their hospital home, and their 5-year old son, Little Walter, passed away from it two days before Christmas, 1895. Following the family’s recovery, Dr Bunn never completely returned the hospital to its previous capacity. The newspaper reported that Dr Bunn had plans to reopen, but that never seemed to materialize.

Beginning in 1895, Dr and Mrs Bunn began to repeatedly place notices in the newspapers, pleading with the people of Lawrence to settle their outstanding debts with the hospital. The family continued to rent “Bunn’s Grove” out for picnics, BBQs, religious tent revivals, and tabernacle meetings. Some of the revival meetings drew hundreds and lasted for several weeks at a time. During his quarantine, Dr Bunn wrote a book called “What to Do Until the Doctor Arrives” that was so well received that he was made Surgeon General of the Kansas National Guard. (The book can still be found on several antiquarian book sites, and can be downloaded free online. It’s pretty interesting.) But none of these things brought in enough money to sustain the property. The Kansas Guard asked Dr Bunn to accompany a unit on a relief mission to the Klondike in 1898. Thinking he might strike it rich at one of the Alaskan goldmines during his mission, he agreed to go.

A few months after his departure, Mrs Bunn delivered a baby boy, and the family eagerly waited for the doctor to return. Mrs Bunn continued to place ads pleading for the payment of outstanding debt to be paid, “as business requires it.” Seeing the repetition of the notices in the papers is a little depressing. Knowing that her neighbors in this small town were not paying her for the medical services they had been so generously given in times of need made me so sad for her. Apparently, she was ignored and the property was placed on the delinquent taxes list. That same month, she was notified that a lawsuit had been filed for nonpayment of gas, fuel, and lighting bills. Days later, the property was listed on the delinquent tax auction list.

Heartbreakingly, Mrs Bunn had a lot on her plate. Dr Bunn had been gone for more than a year and a half, and his letters had not been reaching home. The child born after Dr Bunn left died tragically after getting into his father’s medicine chest and overdosing on headache powders. Months later, Dr Bunn returned home, penniless. He had lost everything in a fire in the Klondike. Needless to say, he did not strike gold. The Bunn family must have felt completely broken. Despite recurring illnesses, Dr Bunn attempted to revive his failing medical practice. His health was in rapid decline, and he appeared to be completely dejected. His official diagnosis was Bright’s disease—a chronic kidney disease. The Lawrence Daily Journal hints that the property is at risk for foreclosure in that it reported that a committee had looked at the house/hospital as a possibility for a trade school, but it was never mentioned again.

Dr Bunn died in December of 1900, and Mrs Bunn tried desperately to sell the property. She even tried to trade it– and offered a generous deal and the best terms possible– but had no acceptable offers. Had Dr Bunn’s life insurance policy not paid out ahead of schedule, the property would’ve been sold at the 1901 county auction (though it appears that her payout was only a fraction of what she had thought the policy was worth). Mrs Bunn paid her taxes and re-bought the tracts she had sold off. She continued to rent out the grounds for outdoor functions, regular tent revivals, picnics, BBQs, and regular celebrations hosted by the AME Church. She converted the hospital back into a house, and had a telephone installed with her own, private telephone number (I love that her telephone number was “Red 819” and that it made news that she got a phone!). Over the years, she got behind on her property taxes a few times, but always seemed to catch up again.

Until 1921. That year, the property was sliced into five pieces and sold at auction. A man by the name of Glen Nickel reportedly moved his family into the home, but then the trail goes cold. I couldn’t find any further mention of the house, the property or any events, picnics, revivals, BBQs– nothing.

The next time the house I found the house mentioned in print is in the 1928 autobiography of Col. W. A. Starrett, titled, “Skyscrapers and the Men who Build Them.” Col Starrett was William and Helen’s youngest child, and he was only three years old when the family left Kansas. After WWI, he was in Kansas on some military business, and he stopped by the old place for a look around. As he walked through the abandoned home his father had built, he noticed his father’s though throughout the construction of the house. In reading the passage, it’s easy to sympathize with his feelings about the dilapidated state of the house in which he’d been born. The leaky roof, crooked and broken shutters, and front door that had been carved with such precision and hanged with care. The great windows that had once been a source of so much sunlight had all been dirtied by years of neglect and broken by decades of mistreatment. All the windows, except for one.

As he turned to walk out the front door, Col Starrett noticed that the transom window above had somehow remained undamaged. He made arrangements to secure the cherished family heirloom, and had it sent to his home in New Jersey.

The house that William Aiken Starrett built in 1864 was torn down sometime during the 1940s. The stones he’d had quarried and numbered and charted from the nearby creek were used in the construction of another residence in town, and the rest was hauled away.

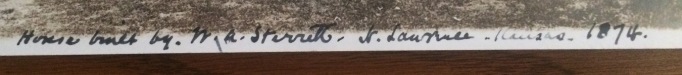

Nothing remains of this amazing home but the few photographs I found in Helen Starrett Dinwiddie’s personal papers in the 1990s (Helen was one of the two Starrett daughters born in the house). The photographs were taken shortly before the house was demolished, but I don’t know who took them. They are small in size– only 1″x 2″, and there are no negatives (all of the photographs, except for the one at the beginning and the copies of the transom window are from this collection). Helen also left behind the beginnings of her own autobiography, part of which I used to create this “biography” of the house.

Helen was my great grandmother—William Aiken Starrett and Helen Ekin Starrett were my great grandparents. I had rather hoped for a more happy ending to the saga of “The House in Lawrence,” but at every turn, I was further saddened. Except for the tale of the transom window.

For 25 years, I have encountered Starrett relatives and inquired about it. No one seems to know what happened to it. For 25 years, I have searched for it. It is my Holy Grail. It is my Everest. Someday I hope to find it. If its owner is family, I will be happy, and (somewhat) satisfied with a photograph. If it’s owner is not, then I will do my best to bring it back into the family—where it belongs.

P.S. If you are reading this and you are a Starrett family descendant, please feel free to contact me! I’ve received many emails from distant cousins, and I love that William and Helen’s great great grandchildren (and further down the tree!) are connecting! If you have any knowledge of the whereabouts of the original window, please, please, PLEASE let me know. I would love it find it. If it’s out of the family, I’d love to bring it back in. If it is in the family, I would dearly love a photograph of it– and possibly a rubbing of it– so that I can have an exact duplicate made. THANK YOU! Julie Dirkes Phelps

ALSO! If you have any photographs of the House in Lawrence that do not appear above, please send me digital copies so that I can add them to the history of the home. I was also unable to locate any photographs of the Bunn family. I would love to include them as well.

© Julie Dirkes Phelps

Photographer, Author, Researcher, Archivist, and Storyteller.

© Copyright 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, reposting, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without prior written permission. Be cool, don’t plagiarize. If you want to use something, just ask.

Oh my goodness, Julie … I am crying my eyes out! What beautiful stories – but what heartbreak, too. It seems so monumentally unfair that people like William Starrett and Dr. Bunn, who were so devoted to their families and to serving their communities, should both fall on such terribly hard times. [Gets up to grab tissue.] And to then read that the house was demolished! It’s difficult to imagine that such a monument to love and the seat of so much history and happiness could just be torn down. [Gets up to grab another tissue.] Thank you for the most wonderful piece of writing I’m likely to read today. Your research and the quality of your storytelling are just astounding. I hope you will consider collecting all these posts and seeking a publisher at some point (maybe a historical or university press?). Because … wow. Just, wow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading your comment first thing in the morning is the best way to start my day!!!! I cried while researching too. I remember finding out that the house was torn down (I found out in about 1993) and it broke my heart. The rest of the story I just learned in the last few weeks. It just kept getting sadder and sadder. I wanted a surprise ending like “oops! The house actually IS still standing!” But no such luck. The old Grove is covered in a subdivision. I think. I can’t even tell. Seeing the bankruptcy record just…. Ugh.

Actually, I’m VERY interested in having all of it published. Hopefully I can find someone! And I’m trying to talk the hubs into a road trip to Kansas. It’s only 11 hours from Austin to Lawrence!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not surprised to read how emotional the research was for you, Julie; it really shines through in your writing. And I’m thrilled to read that you’ll consider having this history published when you’ve gathered all the stories you want to tell! It’s really extraordinary writing, and it deserves a wide audience. I’m not terribly well connected to the publishing industry, but I’ll be very happy to inquire with the few contacts I have on your behalf when the time comes.

PS: Please forgive my delay in replying. I was traveling and the wi-fi was spotty. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much!!! Your comments mean the world to me!

LikeLike

Hi! I just found your comment on my posts about my father Eddie Green and my New Laptop!. For some reason your comment went into my Span folder. Glad I checked. I’m so glad you like the stories. It’s late now so I will continue reading your above post tomorrow byebye

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Julie,

It’s Janice from Reflections. I don’t know if you are aware, but I am a history teacher. I teach Medieval Times.

Janice

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was great to come upon your story! I have been trying to get more information about North Lawrence; specifically where my house is located. I am pretty sure that I live on the plot of land or just across the road from where the house used to stand.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh Hannah! If this is where your house is, that would be so wonderful! Please, let’s keep in touch so that when I come to NL I can meet you and see the land and I won’t look like some kind of lunatic aimlessly driving around the neighborhood. Plus I’ve been dying to meet some people in the area so that I have some friends when I do visit…. I feel like I know the area SO WELL, but I only in terms of more than years ago! Look through my blog– there are more stories about Lawrence in here.

LikeLike

And Hannah– my email address is the name of my blog (all one word with no punctuation) at yahoo dot com (if I type it all out, it’ll be a spamathon!) -J

LikeLike

I sent you a message; hopefully I sent it to the right address!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I just saw it. I’ve been swamped. I’m emailing you back.

LikeLike

Hi Julie, thanks for sharing this! As a physical therapist, and author of Your Body Book Guide to Better Body Motion with Less Pain, to look up this history of my great grand father, who wrote What to do until the Dr comes, is fascinating. Dorothea was my grandmother, my name Doranne was a compilation of Dorothea and Dianne, my mother’s middle name. Thanks again, Doranne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Doranne! You must be related to Walter!!! He and I have joked that we are “related by house.” It broke my heart to learn that the house is gone. I know Walter feels the same. By any chance do you have any photographs of the house? As far as I know, the ones included in the post are the only ones, and I have the only copies of them (passed down to me in an envelope that says “no negatives”). I’m hoping (fingers crossed) to go to Kansas this summer.

Julie

LikeLike

My great grandfather, John Starret, was William Aiken Sr’s brother. John followed his brother to Lawrence at some point. I still live in the Lawrence, KS area. I don’t know where your holy grail ended up. However, have you read Paul Starrett’ book “Changing the Skyline.” The first house that William Sr lived during Quantrill’s raid is discussed on page 7. It’s still in existence and is on the Historical Register. I drive by it about once a year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

OMG Linda!!!! PLEASE SEND ME AN EMAIL!!!! My email address is (I’m typing it all out so the spammers don’t lift it!) itsabeautifultree at yahoo dot com. PLEASE EMAIL ME!!!! Since I wrote this, I’ve been to Lawrence twice! I really want to go up to Lawrence again, and I’ve been working on another project that has me temporarily sidetracked. But I can’t tell you how excited I am to read this message from you. I really need to write a follow up to this piece as well, but I really want to talk to YOU!!! Send me an email and we can chat. I’m so crazy excited!!! —Julie

LikeLike

Hello, Linda! Do you know whether William & Helen’s first home on Rhode Island was where Susan B. Anthony stayed in 1867? OR did SBA stay at their home on corner of 11th and Kentucky? She probably visited them at the “Castle” in the 1870s, before they moved to Chicago. Let’s do lunch in Lawrence!

LikeLike

SBA lived with them at the “Castle” in North Lawrence. She was there for quite awhile and visited sporadically afterwards until they moved to Chicago.

I am so sad that the house is gone. There were two other houses built from the stones though. One of the houses I’ve seen (and touched, and the owner thinks I’m certifiably crazy for asking him if I could touch the outside of his house, but I just HAD to touch it!). The other house I’ve seen pictures of, but I’m not 100% sure of where it is. I’d hoped to have found more pictures of it in the Douglas County Museum, but the only ones they had were ones from my private collection (posted online). They had one that I didn’t have, but they wouldn’t allow me to have a copy of it. I’d love to know if there are more images of the house in any other archives or collections in town. I’d give anything to know where the front door ended up. It’s exquisite, and I’m sure William carved it himself. The transom window is in a house in New Jersey, and the house was recently up for sale, but the realtor wouldn’t return my calls, so I’m not even sure if it’s still there.

I have made friends online with a descendant of Dr Bunn, the man who bought the house and then turned it into a private hospital. I know he’d love to see pictures of it too! We jokingly say that we are “family by house.”

The house on Rhode Island was where Helen and William lived when they were newlyweds, before they bought the North Lawrence property (shortly after the Quantrell Massacre). They’d rented the second floor, but, it’s my understanding that they were told that the whole second floor was a bit too grand for a minister and his wife (with no children yet) so they gave up all but two rooms, I think.

LikeLike

Hello, Julie! What extraordinary great grandparents you have!! Would love to share with you more history I’ve written on Helen and William Starrett during their years in Lawrence, Kansas (1864-1880). Please contact me when you can.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They were pretty amazing, weren’t they! When I’m feeling lazy or unmotivated, or when I just don’t feel like doing anything at all, I jokingly say that I’ve got “used genes.” They’re all used up because Helen and William did ALL THE THINGS, and what they didn’t have time to do, their kids did, so the genes we all inherited are all used up! Of course, I’m kidding– I see my “lazy time” as taking all the breaks Helen should’ve taken! HA!

I really really REALLY want to see what you’ve written on Helen and William in Lawrence! I was able to get a lot on line, and a little more while I was in LFK in the summer of 2017, but I didn’t have enough time or any connections to really locate the meat of what I needed. I’d love to collaborate with you on their time there. My email is itsabeautifultree at yahoo dot com (spammers just have to make everything difficult, don’t they?). I look forward to hearing from you!

Julie

LikeLike

I can snail-mail you a whole packet of Stuff with LOTS of meat! Would you like me to forward all Lawrence news articles she wrote by email, or print them out and mail in package? (I lost count over how many she wrote in 1870s.) All for your Christmas/New Year’s reading pleasure. Jeanne

LikeLike

I would LOVE that! You can either send by email or print, whichever is faster/easier for you. I know I can print a ream of paper in the time my patchy internet allows me to upload most attachments, but either is more than fine by me. Shoot me an email at itsabeautifultree at yahoo dot com and I’ll send you my snail mail address. I’m really excited to see what you’ve got! It’s been a little frustrating digging through the various newspaper sites trying to patch together all of her writing. She wrote so much!

LikeLike

RE: Which house SBA stayed at in 1867 (before visiting North Lawrence home). When Rev. Starrett became Supt. of Douglas County schools in 1868, they lived in house (w/his office) at 11th and Kentucky (by Feb.). Not sure which corner, but it could be a parking lot (see google maps).

LikeLike