Six Sioux Chiefs in the Jail Yard

Part Ten—The Trial

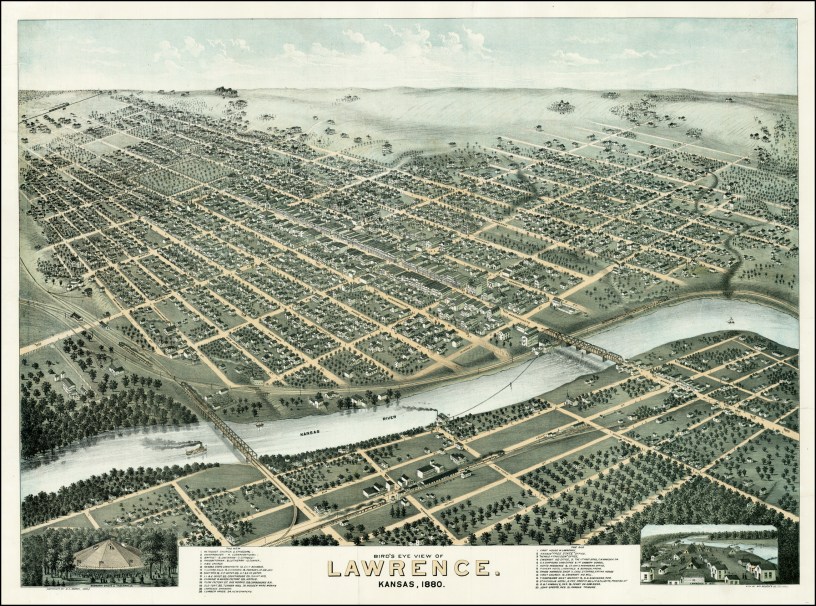

On October 10, 1879, Agent John D. Miles arrived in Lawrence, Kansas, for the trial of the State of Kansas v Wild Hog et al with the defendants’ families. The large group checked into the Lawrence House, one of the nicer hotels in town.

Several government agents, an interpreter, Old Crow and his family, and Wild Hog’s family had all traveled to Lawrence for the trial. The women refused to interact with anyone outside of their own circle, and when they were approached by outsiders, they shielded their faces with their robes. The children were lively, mischievous, and were said to be a bunch of smart and cute little kids—and there was a lot of buzz about the chiefs’ beautiful teenage daughters.

After registering at the Lawrence House, Agent Miles took everyone to the jail for a visit. Once the men had been reunited with their families, the whole group went out into the jail yard and gathered in a circle as a family just outside the door. Together for the first time in eight months, they smoked a big pipe, and silently prayed. To the Northern Cheyenne, smoking the pipe together is a solemn occasion, and is only done following a prayer. The rising smoke from the pipe that day would’ve been an act of communion with the spirits in anticipation of the court date they’d been so patiently awaiting since they’d been taken into state custody almost eight months earlier.

Wild Hog appeared much happier and more relaxed while in the company of his wife and children. The Kansas Tribune reported that the sight of him with his family was moving, and that he showed an emotional depth and tenderness emotions which “savages” are rarely given credit.

The Trial

The next day, Captain Jeremiah G. Mohler accompanied his clients to the Douglas County Courthouse to begin the proceedings. At 4:00pm on October 13, 1879, Douglas County Judge Nelson T Stephens called to order the first degree murder case of the State of Kansas vs. Wild Hog et al.

Defense attorney Mohler, Wild Hog, Porcupine, Tangle Hair, Blacksmith, Noisy Walker, and Strong Left Hand patiently sat in court and quietly waited for Ford County Attorney Mike Sutton to arrive. Once the Mohler entered his clients’ “not-guilty” pleas, they’d head back to the jail to rest up for arguments and testimonies to begin in the morning.

Ford County Sheriff Bat Masterson had taken the men into civil custody at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on February 9, 1879. The State of Kansas indicted them on first degree murder charges at that time. For more than eight months, they had patiently been prisoners in the jails in Ford and Douglas Counties while the wheels of American justice slowly turned. And now, October 13, 1879, it was finally time to put an end to it. They stoically sat in the courtroom with their lawyer, the man who had confidently stood by their side and been loyal to them, and they waited.

And they waited.

Ford County Attorney Michael Westernhouse Sutton was a no-show.

Mike Sutton, the man who, on the 15th of January, 1879, wrote an emotionally charged two-page letter to the Governor of Kansas, demanding that the “predatory savages” be punished for their crimes, and that “the people expect and demand, as they confidently believe this matter will receive prompt and decisive action at your hands,” allowed six men to sit in jail for eight months, and then didn’t show up for the trial. The man who Ford County, Kansas, trusted to prosecute the men who they believed had wronged them so heinously just didn’t show up for the trial. Mike Sutton allowed the families of the victims of the depredations—and actual victims themselves—to believe that he was diligently doing his job and pursuing the men he went to great effort and expense to apprehend, identify, and incarcerate, and he didn’t even bother to show up in court on the day of the trial.

Instead, he sent a letter. A letter.

Ford County Attorney Michael Westernhouse Sutton had been busy with other things.

So what, exactly, had been more important?

In April, Miss Florence Estelle Clemons had come out west to Dodge City, Kansas, from Gloversville, New York, to visit some friends and to see her uncle, Mike Sutton’s associate, Mr. A.B. Webster. The pretty young twenty-year old had captivated the bachelor County Attorney—who was eleven years older than she was—and the two had fallen in love. The couple’s friends had expected to get a wedding invitation in the mail at any moment, but Mike and Stella surprised everyone.

On the afternoon of October 1, 1879, Mike and Stella tied the knot in the parlor of her uncle’s fancy new Dodge City home. The simple, private ceremony was officiated by Mike buddy, newspaperman N.B. Klaine. Later that evening, the newlyweds snuck out on the night train to Kansas City and St Louis for a romantic honeymoon. Nine days later, Mr. and Mrs. Sutton returned to Dodge City and took up housekeeping in a home near the courthouse.

Mike was a popular guy in Dodge City. Several of his lawyer buddies, including Mayor James H. “Dog” Kelly, his partner E.F. Colborn, Samuel Marshall, and Harry E. Gryden (the same Harry E. Gryden who’d been the lawyer that Agent Miles originally pegged to defend the Northern Cheyenne) decided that there was no way they were letting their pal Mike get married without a proper celebration. At 8pm on October 11, 1879, more than two hundred of Mike Sutton’s nearest and dearest gathered in celebration. Following the initial music and speeches, the party thinned out and moved on to “Kelly & Beatty’s place,” where they drank cold drought into the wee hours of the night.

Back to the Trial

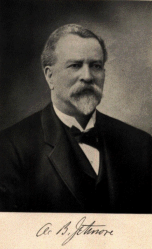

Just after Judge Stephens called forward the case of the State of Kansas v. Wild Hog et al., a tall, dark haired man entered the courtroom and approached the bench. Mr A.B. Jetmore was fresh off the train from Topeka, having been sent to Lawrence by his partner, State Attorney General Willard Davis. Mr. Jetmore informed the court that he was expecting evidence, but as he had just received the case the day before, he was requesting a continuance of one week so he could familiarize himself with the details, review the evidence, and interview witnesses.

Capt. Mohler immediately objected. He read his defendants’ papers to the court and explained that they had been ready for trial since the change of venue had been granted back in June—eight months earlier. The defense argued that in those months, Mr. Sutton, Ford County, and any other prosecutors they wished to use, had been given more than sufficient time to prepare their case, and that another week’s continuance would cause undue hardship and expense to his clients and the approximately forty witnesses who had traveled to Lawrence specifically for this case. Capt. Mohler had issued subpoenas to more than two dozen people, including Army generals and the Secretary of the Interior. He argued that if he’d been able to do all of this, that the prosecution should’ve had sufficient time to do the same.

Mr. Sutton’s letter to the court explained that his witnesses were spread around the country, and since they were in Texas, Nebraska, and Arizona, they had been unreachable. The defense laughed at this notion. Judge Stephens agreed with Captain Mohler and censured the prosecution for its lack of diligence. The State’s motion for continuance was denied. They would either begin immediately, or enter a plea of nolle prosequi.

Then, on behalf of Ford County and the State of Kansas, Mr. Jetmore had no choice. He had no clear understanding of the case, no evidence, and no witnesses. He had been put in a no-win situation. With no other option, he entered a motion of nolle prosequi.

Nolle prosequi. According to law.com, nolle prosequi is Latin for “we shall no longer prosecute,” which is a declaration made to the judge by a prosecutor in a criminal case (or by a plaintiff in a civil lawsuit) either before or during trial, meaning the case against the defendant is being dropped.

After everything Wild Hog, Porcupine, Tangle Hair, Blacksmith, Noisy Walker, and Strong Left Hand had been through, Ford County was ceasing their prosecution, and the men were free to go.

Just like that, it was over.

Judge Stephens asked if there was anyone who could take the Indians into custody so that they could be returned “home” to the Darlington Agency at Ft Reno in Oklahoma. Agent Miles rose and stepped forward and claimed responsibility for the prisoners.

The interpreter translated everything to the men as it happened. Once they understood that they were free to leave the courtroom as free men, Wild Hog, Porcupine, Tangle Hair, Blacksmith, Noisy Walker, and Strong Left Hand momentarily stood in stunned silence. It’s unlikely that they fully understood what had just happened (I don’t think anyone would in their situation—I don’t fully understand, and it’s been over 130 years!). Surely, they had expected to leave the courtroom in chains, destined for the scaffold. But now, they were told that they were no longer being charged. Then, without emotion, each man walked forward, one at a time, and took Judge Stephens by the hand. Every single one of the Northern Cheyenne former prisoners quietly thanked the judge and each of the lawyers before exiting the courtroom.

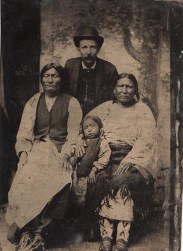

When they left the courthouse, they were, for the first time in nearly a year, almost free. They were no longer in irons and no longer being returned to a jail cell. Agent Miles and Capt. Mohler accompanied them to the Lawrence House where Crow and the wives and children were anxiously awaiting news from the courtroom. They privately shared the news with their families. While Agent Miles made arrangements for their return to Oklahoma, they rested at the hotel. Before leaving town, the group had their photograph taken by Lawrence photographer, W.H Lamon, in his studio. On their way home, they stopped in their attorney’s hometown of Salina, Kansas, for a “pleasure trip” for few days before continuing on to Darlington, Oklahoma.

The Northern Cheyenne prisoners’ day in court seemed anticlimactic. But, somehow, everyone’s general feeling was that the senselessness just needed to stop. It was obvious that the wrong people were continuously being punished, and October 13, 1879 brought an end to a lot of it. Without formally saying so, it was almost as though the universe was saying, “enough.”

The case of the State of Kansas v Wild Hog et al. was significant in that it changed that way Native Americans were legally charged in the court system—individuals were no longer charged for the actions of tribes as a whole. And reform was brought about that no longer permitted entire tribes to be tried for crimes committed by individual members.

And during their imprisonment, the overall sentiment of the nation shifted. White Americans began to see the wrongs that had been done— and were still being done— to the Native Americans, and they started to become aware. Though policy changes and personal sentiments were still evolving, this case marked a change in the overall sentiment. Some settlers were still afraid of Indians on the Plains, and racism was still apparent, but eyes were beginning to open. So much damage had already been done, but Americans were starting to see what was happening, and it was a start.

In the end, no one really won. The murdered settlers, the raped women and girls, and the devastated families were barely, if at all, financially compensated by the state or the federal government. Most of their depredation claims were denied outright. The Northern Cheyenne people had been virtually exterminated, and their ordeal was scrutinized from every angle. Native American leaders and sympathizers began advocating non-violently for Indian rights. Reform efforts for Indians and their tribal lands began to shift. And new histories from different perspectives began to be recorded. The hardest part about finding out what actually happened during this time is that there are so many differing accounts—the government’s, the settlers’, the Northern Cheyenne, the media… no two are the same.

And that’s probably why, over 130 years later, the story isn’t well known. That’s why it’s probably so hard to figure out what really happened. And it’s probably why relations in this part of our society are still in fluctuation—especially when it comes to issues regarding the Black Hills. No one knows what happened, why it happened, why it started, and what can be done now, a century later, to make everyone happy.

Now I know. And so do you.

But now I know who Paul meant by the “six Sioux chiefs” in the Lawrence jail yard. Now I know why he was a confused kid, afraid, but amazed by the sight of the Indians, especially Wild Hog, who, at 6’5” was probably the most awesome and frightening and majestic and amazing and exotic man he’d ever seen. The Indians, with their blankets and long, dark, hair and tanned skin, so different from the intellectual, Yankee educated farmers and thinkers he’d been surrounded by his whole life must’ve captivated his imagination. They obviously made an indelible impression on him and his siblings, and the rest of the country—and they would continue to do so for generations to come.

© Julie Dirkes Phelps; Photographer, Author, Researcher, Archivist, and Storyteller. © Copyright 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, reposting, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without prior written permission. Be cool, don’t plagiarize. If you want to use something, just ask me. I try to make sure to attribute all images to the appropriate sources, but sometimes I inadvertently post an image from an incorrect source (or the image is incorrectly cited from my source), get images mixed up, or accidentally leave something out. Please email me at itsabeautifultree@yahoo.com with any corrections or concerns. Thanks.

(A quick note on the photos– my file containing my photo sources was corrupted, so I had to go by memory in crediting sources. My sincerest apologies if the sources are incorrect! I didn’t want to hold up posting because I’ve had messages asking for it! I hate cliffhangers too!) Photos: Map of Lawrence, Library of Congress • Douglas County Courthouse, Kansas Memory • Wild Hog’s family, Ameritribes; JG Mohler, Pinterest (original source unknown) • MW Sutton, Kansas Memory • AB Jetmore, Find a Grave • The Lawrence House, origin unknown • Group Photo, Kansas Memory via pinterest (posted in multiple locations) • Raid Survivors, multiple sources • Porcupine, pinterest (original source unknown) • Old Crow, from Grinnell’s work on the Cheyenne, Library of Congress • Memorial of the Last Raids, Kansas Memory and Library of Congress via Pinterest

OH, WOW … I didn’t see *that* coming! As relieved as I was to read the plea, it somehow added to the meaninglessness of everything Wild Hog, Porcupine, Tangle Hair, Blacksmith, Noisy Walker, and Strong Left Hand had endured up to that point. And your summation of the importance of this case was just beautiful!

Well, thank you for sharing this extraordinary story with your readers. I feel very privileged to have been able to join you in discovering who Paul’s “Six Sioux Chiefs” were. What a story! What a story …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you believe it? That is really the way the whole thing ended. That’s why I went crazy researching because I thought it was a mistake!!! It was like everything was for nothing. Like the worst Hollywood ending ever. And because of the good ol’ boy network, he just walked away.

Thank YOU for following along and cheering me along this journey! It still feels unfinished, but unless Doc Brown and the Delorean show up, I’ve just got to let it go. I need a happy story next!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha! Perhaps Doc Brown *will* show up and you can go back to make a few “adjustments.” I would like to read how THAT story ends very much indeed! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d change so many things!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’re there court transcripts of the trial or court notes? Any idea how the defense attorney came to represent the defendants? Proud relatives of translator George Reynolds

LikeLiked by 1 person

That I can’t tell you! If memory serves me correctly (it’s been awhile since I wrote this and I’ve been totally immersed in another project!) I wasn’t able to find court records/transcripts, that to do remember for sure. The information I was able to piece together came from the handful of books I listed in my sources and in the newspaper articles that reported on it in the various newspapers (I think I bought every book on the Cheyenne that I could get my hands on!). The US government’s behavior was so reprehensible from beginning to end in this episode that it was a bit of a treasure hunt to find what I did! As more and more documents are made available online, more cool details may surface (that will be searchable, which makes ALL the difference). Pretty awesome about your relation to George Reynolds. The translators often had interesting stories as they had such divided loyalties. I enjoyed researching the Cheyenne. I’ve been eyebrow-deep in the Osages for a few years now and focusing on specific tribes is more interesting and rewarding than most people of non-native descent realize.

LikeLike