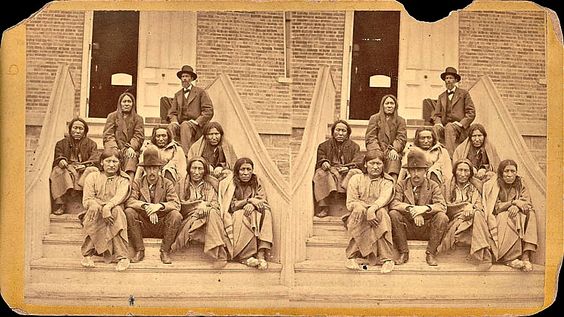

Six Sioux Indian Chiefs in the Jail Yard:

Epilogue, Thanks, and Sources

Throughout the ten parts of “Six Sioux Indian Chiefs in the Jail Yard,” I tried to keep a neutral position and just tell the story. I’m VERY easily distracted by footnotes, endnotes, and the little numbers telling you where to find stuff, so I intentionally left that stuff out. The way I tell stories, I think those distractions take away from the experience. So, now that the series is done, I’m going to editorialize and reveal all my sources and share my backstory. So, without further ado…

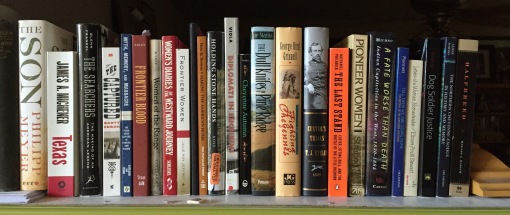

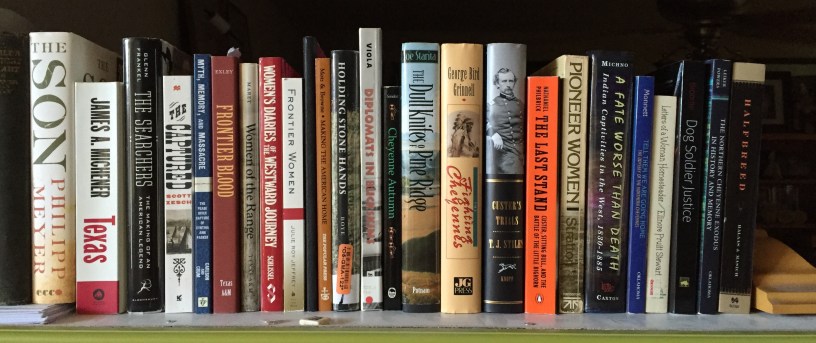

As I said in Part One, I didn’t have any idea what I was getting into when I started writing about the Northern Cheyenne. But I’m really glad I did. I learned a lot. Right now, I have 15 books sitting on the table in front of me. Of the fifteen, I’ve read six of them from cover to cover, leafed through five of them, and picked through the remaining four. I dug through hundreds of vintage cowboy magazines at The Book Cellar in Temple, visited three different Half Price Books locations in Austin, and had UPS here every other day delivering books from Amazon Marketplace (ranging in price from a penny to ten bucks). I read six-years worth of reports of the Commission of Indian Affairs, and met (via Facebook) this amazing researcher/Western aficionado/author/editor the American West in the UK from the English Westerners and a few members of the Northern Cheyenne tribe.

I can’t believe that I’d never heard this story before. I had no idea that any of this happened in our history, and it made me angry. It made me angry about all of it. Angry about the treatment of the Native Americans, angry about the treatment of the settlers, angry about all of it. And since the United States is in the throws of a national presidential election, it made me hate national politicians and public policy and red tape and government bureaucracy and the concept that our government leaders make decisions from their offices hundreds of miles away based on stupid reports that don’t tell the whole story.

Most everything I read about this mind-boggling chapter of history ends with the trial. The charges were dropped due to lack of evidence, and then it was over and then everyone went home and ordered a pizza. But we all know that there is always more. There is always more than “the end.” I’ve been plagued with so many questions about this. Sadly, I was not surprised at everything that led up to the trial because it’s well documented that the Native Americans were treated so terribly for so long—treatment that, in many way, continues today. The part that just really felt unfinished was the trial itself and its aftermath. Why? Why didn’t Mike Sutton show up? WHY?

Nothing much is written about any of the players from the trial about their involvement in it after the trial was over. We know that the court released the six men into Agent Miles’ custody and that he took them back to Darlington in Oklahoma. Wild Hog disappeared into obscurity. He did return to Oklahoma, but when the Northern Cheyenne Reservation was established in Montana in 1884, his name never appeared on any of the registers there. I was unable to find anything on Strong Left Hand, Old Crow, Blacksmith, or Noisy Walker either. A photograph of Tangle Hair and his granddaughter was published with George Bird Grinnell’s work in the 1920’s, but other than that, I didn’t find anything else about his later life. Porcupine became active in the Ghost Dance religious movement, traveled to Washington DC, and participated in diplomatic negotiations, and was photographed several times. He became a “chief” and was highly respected within the tribe.

Agent John D Miles was another one that I was wondering about. He was a Quaker who was hired because he was a Quaker. He spent his entire career either as an agent in the employment of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs or as a lawyer for the Indians. He was accused of allowing cowboys to illegally graze on the Indians’ lands and of owning a share of one of the trading posts that operated near Darlington that price gouged the Indians, but it seems that he was probably just a scapegoat of the federal government. From the reports that I read, It looked like Miles tried to do the best that he could with the crap he was given by the government. It’s hard to care for thousands of people who don’t want to be taken care of without enough resources at your disposal. I mean, the Indians were forced onto the reservations in the first place, and then Miles gets blamed because the government doesn’t give him enough food to feed everyone. I was surprised to find out that he had been married the whole time he was at Darlington and that he and his wife, Lucy, had three children, and that they all lived with him on the reservations. His son was even born at Darlington in 1875. Agent Miles and many of his family members are buried in Lawrence Kansas at a the same cemetery as one of my 3x great grandmothers.

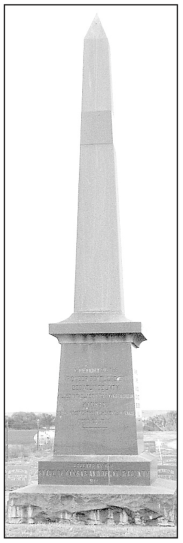

Now, the European immigrants. The European settlers in western Kansas were new immigrants who been unaware of the situation with the Indians, so they felt deceived by the entire episode. They thought the Indians were all friendly, and the ones approaching them were just asking for food—and they were prepared to share! (Knowing the Czech culture here in central Texas, I think this would’ve all been different had the Northern Cheyenne known anything about kolache. But I digress.) In Oberlin, Kansas, there is a monument in their memory. Since the Northern Cheyenne faced one horror after another, the stories of the Bohemian and Czech settlers are often forgotten, and that’s sad.

By 1884, only 26 of the 116 depredations claims the government approved were actually paid. That’s nauseating. The States of Kansas and Nebraska never even considered paying from their own coffers— they expected the feds to do it. There was one case brought by Milton C. Connors in Nebraska that was denied, so Connors took it all the way to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court acknowledged that the depredations were instigated by the treatment the Northern Cheyenne had suffered at the hand of the government, and that it was not legal for the tribe to be financially liable for compensation. (Yeah— the government actually expected the Indians to pay claims from their already deficient funds. They already didn’t get enough food, and now they had to dip into that budget to pay for damages. One one hand, it makes sense, but on another, um, no.) The depredations claims that were eventually paid were only for material losses, not the loss of life or compensation for medical treatment or the psychological ramifications from the traumas inflicted. Nice. Especially considering how women were viewed and treated back then.

The loss of property was staggering. Homes and their contents were burned, cattle were killed and stampeded, and everything that could be broken and destroyed was broken and destroyed. Claims were made for everything from books of matches to library books, clothing to mattresses, sewing machines to farm equipment, medication to stamps and money. On one farm, a herd of sheep was slaughtered and left to fester. Crops were destroyed by roaming livestock. And, the survivors were displaced to neighbors’ homes, so some families ended up housing, feeding, clothing, and supporting their friends— another financial strain.

The innocent settler victims seem to get forgotten in the story, so I’m going to list the ones I could find from the reports here: Ed Miskelly, N. Dowling, Alexander Foster, Jackson Leatherman, John Young, James G. Smith, Ferdinand Westphal and his son, R. Bridal, Ephraim Humphrey, William Laing, John Laing, William Laing Jr, Freiman Laing, Marcellus Felt, George F Walters, Moses F. Abernathy, John Irwin, Mr Lull, John Wright, George Abbott, Hynek Janousek, Peter Hanousek, Rudolph Springler, Frank Rochor, Arnold Kubitz, Anton Stenner, George Fremby, Fred Hemper, Mr Morrison, and Mr Zeidler. The women and girls who were raped (and had the guts to it) were Louise Van Cleve, Eva Van Cleve, Julia Laing, Mary Laing, Elizabeth Laing, Mary Janousek, Barbara Springler, Catherine Vocasek and Mary Kubitz. Many others were seriously wounded. One of the women was rumored to have been impregnated during the raid, and her child lived with those rumors for her entire life. Catherine Vocasek’s husband asked for depredations for himself because of the shame he had to live with following his wife’s rape (what a peach!). Julia Laing and her daughters left Kansas. Julia’s husband and all of her sons had been murdered, two of her daughters had been raped, and her youngest daughter watched it all. Nice. I read that the Laings moved to Canada. I would’ve too—hasta la vista, America. I would’ve given Uncle Sam the flying bird salute if my family had gone through what they Laings went through and then been denied depredations. All of these widows were left without homes since their properties had been destroyed in the raids, and they had no source of income or support. Unless and until their claims were paid, they faced destitution. Many of the survivors left Kansas and scattered around the country and became dependent on their families because the government screwed them.

In some of the rape cases, the families felt so much shame that they moved away and never spoke about it again. Some of the young girls had psychological scars that never healed. Julia Laing and her daughters moved to Ontario. The Vocaseks were said to have moved to Virginia. Perhaps it was their own exodus from Kansas and/or their unwillingness to testify in court that made Sutton’s case fall apart. Maybe he couldn’t find them, maybe they refused to talk, or maybe he just didn’t try hard enough. Back then, the aftermath of rape was much different from how it is today, and the women would’ve found it incredibly humiliating to stand up in court and relive their experiences, even if it meant that the men would hang if they were found guilty. Even though the rapes weren’t their fault, the women were still made to feel shame for what had happened to them. I can’t even imagine.

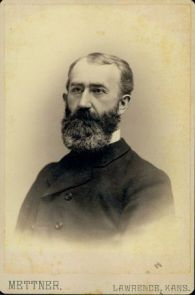

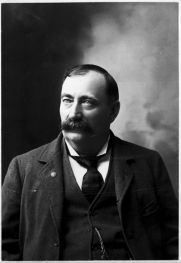

Like I said, I was really intrigued by Mike Sutton and how he could just not show up to court on the day of the trial. Almost everything written said that the case was dismissed for lack of evidence, but it was more than that. He didn’t show up in court and he sent a letter. Why? I wanted to know what happened to him. So when I found his bio, I was pretty pissed off. He had a really great career after the trial and it does look like he just walked away. I haven’t been able to find out whether or not he was actually censured or given a little slap on the wrist (if that), but here’s Mike’s story:

Throughout Mikey’s career, in addition to his other political positions, he concurrently held a position as a lawyer for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad until he died. Less than two weeks before the trial date, he married Florence Estella, or “Stella” as she was called—but in looking at the dates, it appears as though she the wedding may have been hurried along for a reason.

Exactly nine months after their wedding date, their son Stuart was born. When the baby was three weeks old, they were in a serious buggy accident, and Stuart was in a coma for several days. Although he recovered, he sustained a traumatic brain injury and required lifelong full time care. Stella died in 1888 when Stuart was eight years old. Mike was a county attorney until 1882, and after that, he had all kinds of different city and county and state positions. He’d been friends with Sheriff Bat Masterson, but the two argued and ended their friendship (probably because ol’ Mikey screwed Bat out of his fee for his part in the Cheyenne case). In 1886, Sutton, who became a staunch prohibitionist, worked against Bat in the liquor war of 1886. In 1893, he served in the Kansas House of Representatives. At some point, they became friends again.

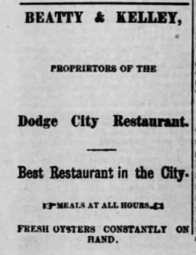

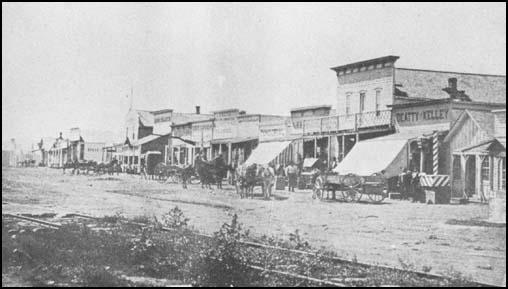

What I found interesting about Mike is that during the trial, all his besties were lawyers, judges, city officials, and politicians. The saloon where the big congratulatory wedding party took place? It was a saloon frequented by “brave men and fair women.” Technically, it was a fancy restaurant, called Beatty & Kelley, but within the restaurant, there was an ice cream saloon run by Samuel Marshall (a buddy lawyer), a barbershop, and a full bar. In other words, after dark, the rough and tumble Dodge City “restaurant” was probably, um, lively. In a description of the festivities, the author said that “cold drought” ran late into the night. Mike may have been a prohibitionist later in life, but in the days following his wedding, it sounds like he was partying with his buddies in Dodge City, and I doubt they were at Beatty & Kelley’s eating ice cream. In looking at the guest list of this party, it’s no surprise that Mike wasn’t reprimanded for his actions.

From what I can tell, all the lawyers, lawmakers and city and county officials were friends. This group was known locally as the “Gang,” led, at one point, by Mayor James “Dog” Kelley. Until the cowboys became too rowdy to handle, the law in Dodge City was were pretty accommodating to them and their behavior. Among Mike’s friends were James “Dog” Kelley, city attorney Harry E. Gryden, Dodge City Times proprietor Nicholas B. Klein, and other lawyers, like the ice cream man Samuel Marshall, Edward F. Colborn, and Frederick Wenie. Alonzo B. Webster, Stella’s uncle, owned the lumber yard and the Alamo Saloon in Dodge City, and he later became the town’s mayor. (Yeah. Stella’s uncle owned a SALOON. I read somewhere that he was involved with some shady ladies, but I won’t get into that!) Bat Masterson and his brothers and Wyatt Earp and his brothers may, or may not, have been part of the group. It seems as though alliances often shifted because Sutton was on-and-off friendly with Masterson and Earp. The families of these all these guys intermingled and socialized too. Let’s see if this makes sense— Stella’s uncle, Alonzo B. Webster (the Suttons were married in his house) was married to Jennie Colborn Webster. Jennie Webster was Edward F. Colborn’s sister. Edward Colborn and Mike Sutton, at one time, had a legal practice together. The wives did stuff together while the men were off governing and lawyering and discussing important things and being masters of the universe into the wee hours of the night. It was a tight group of powerful people.

When things got too rough in Dodge City, the “Gang” started to break up. Or perhaps they just started to grow up and their antics just got to be too exhausting. Whatever. Regardless, the prohibitionists went full force in their crusade against alcohol and gambling, and for whatever reason, Mike became one of them. After the trial, Bat sued Ford County for non-payment of his fees from the Northern Cheyenne case (sheriffs were paid kinda like bounty hunters are today, and the Gang in Dodge just didn’t pay him. And then they ridiculed him in the press for being mad about it. Nice.). Masterson moved on. The Earps moved on. And the Gang moved on and life went on.

So, from all evidence I’ve found from down here in Texas, it looks like Mikey just neglected to do his job because he was too busy dating and doing his thing and being the Big Man on Campus in Dodge City. There was lots of lawyering to be done, and it sounds like there was lots of socializing too. His apparent shotgun wedding, last minute quickie honeymoon, moving in together, and celebratory partying took priority over a bunch of Indians over in Douglas County. Out of sight, out of mind, maybe? And Mike’s buddies weren’t just the kind of friends who could spare a guy from professional ruin, they were also they kind of guys who could save him from being lampooned in the press. His buddy A.F. Kleine ran the Dodge City Times, so he was safe there. (The Globe isn’t digitized, so I’m not sure what they said about him over there.)

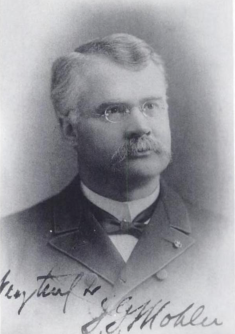

But not all the white guys were underhanded. Jeremiah G. Mohler, the Northern Cheyennes’ defense attorney, seemed like a stand-up guy for the rest of his career. He followed his heart and stood up for people who needed a friend. In interviews, he talked about how he only wanted to give the Indians a fair chance. After his death in 1906, the Salina Evening Journal ran enough stories on him to almost fill an entire page. Everyone admired him for his honesty and loyalty, and was said to have never deserted a client, regardless of their situation. Nothing in any of his obituaries mentioned the work he did with the Wild Hog et al case in 1879. I did find a great story about him in a case involving some men for gambling. J.G. was a judge by then, and the case was brought to his court. Well, Judge Mohler had been involved in this particular gambling case, so after he’d taken all the guilty pleas, he resigned himself and entered his own guilty plea. He told the court clerk to record his fine and have him stand convicted until the fine and court costs were paid. Then he handed the clerk his payment and turned to one of the other guilty parties and said, “Bill, that was your money I paid that with.” HA! What a riot! Judge Mohler served a term in the state legislature. He died in 1904, and is buried in Salina, Kansas.

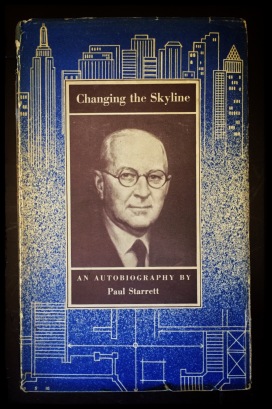

Regular readers of It’s a Beautiful Tree know that Paul (who’s recollection of the six Sioux Indian chiefs in the jail yard started this whole thing) was my great grand uncle, and that he and his brothers went on to do some pretty cool stuff. Paul’s little sister, Helen, was my great grandmother. She also wrote about seeing Indians in Lawrence, Kansas in the 1870s, but her recollections were less specific than Paul’s. The Starretts left Kansas a few months after the trial. Their mother, Helen Ekin Starrett, had accepted a position as the editor in chief of the Western Magazine in Chicago, Illinois. Their father, William Aiken Starrett, opened a law practice in the same building as his wife’s magazine. I write about these guys all the time, so check back for more about them!

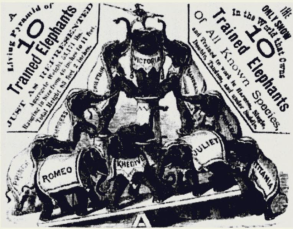

The part about the circus (Part 7) was probably my favorite part of the series, only because it was so serendipitous. I was googling for information about the Lawrence House, the hotel where the Indians’ families stayed while they were in Lawrence. One of the sources that google spit out was my great great grandmother’s publication, the Western Magazine. When I saw the story about the circus, I knew it was about the Starrett family because of the similarities. It was written anonymously (or by the pseudonym “Aunt Mary”) but knowing the family as intimately as I do, it was obvious that it was about them. It pissed me off to see how the circus proprietor took advantage of the boys, but it was pretty cool to see how the situation was remedied. (Oh, and the proprietor in charge of advertising on that leg of the circus was reported to have been a man by the name of Samuel H. Joseph, a career circus promoter during that time. I couldn’t find his picture or I’d out him right now! Justice! Burned by TWO Starrett women! Take THAT, Mr Joseph!)

For the Six Sioux Indian Chiefs in the Jail Yard series, I want to thank the amazing Gary from the English Westerners Society, a really cool organization of Brits in ENGLAND (so I should say “organisation”) who study and write about the American West. Gary sent me a great article from their Brand Book that has been out of print for a long time, and it was a fabulous resource! To Gary Leonard and the English Westerners, I send a hearty ‘preciate-‘cha from here in Texas. Gary has just released a book called Monahsetah: The Life of a Custer Captive. I just ordered it, and I can’t wait to read it!

Also helpful were the members of the Ameri-Tribes message boards. Those guys (and girls) over there definitely know their Northern Cheyenne stuff, and they can identify people like I’ve never seen! Their boards are really interesting, and they didn’t kick me off for asking for help, so, ‘preciate-‘cha!

I love researching, but let’s face it. I’m disorganized, and I am a sloppy with citations. I have seven million screen shots of things that I need to re-name because they have the details for all my citations, but, with that many files titled “screen shot,” it’s hard to wade through. That and my thumb drive of corrupted files with no names at all. That’s why I call myself a storyteller and not a historian. It’s probably why I’ve never gone back to school and finished my PdD! I do have everything written down because I just know I’ll be able to find it when I need it, but then when I need it, I can’t find it. But I do have a milk crate filled with spiral notebooks. So, there you go. Here’s my list of everything I used. The books with bullet points and bold titles are the ones I read from cover to cover. If you want recommendations, ask me which ones I liked and I’ll give you my feedback.

Boyle, Alan. Holding Stone Hands: On the Trail of the Cheyenne Exodus. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 1999.

•Broome, Jeff. Dog Soldier Justice; The Ordeal of Susanna Alderdice in the Kansas Indian War. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 2003.

•Grinnell, George Bird. The Fighting Cheyennes. JG Press, 1995.

Halaas, David Fridtjof and Andrew E. Masich. Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent—Caught Between the Worlds of the Indian and the White Man. DaCapo Press, 2004.

•Leiker, James N. and Ramon Powers. The Northern Cheyenne Exodus in History and Memory. University of Oklahoma, Norman. 2011.

•Michno, Gregory and Susan. A Fate Worse Than Death: Indian Captivities in the West, 1830-1885. Caldwell, Idaho, Caxton Press. 2007.

Miller, Nyle H. and Joseph W. Snell. Why the West Was Wild: A Contemporary Look at the Antics of Som Highly Publicized Kansas Cowtown Personalities. University of Oklahoma, Norman. 1963.

•Monnett, John H. Tell Them We are Going Home: The Odyssey of the Northern Cheyennes. University of Oklahoma, Norman. 2004.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of Little Bighorn. Penguin, New York, 2010.

Sandoz, Mari. Cheyenne Autumn. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 1953.

•Schlissel, Lillian. Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey. Schocken, New York, 1982.

Starita, Joe. The Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge: A Lakota Odyssey. GP Putnam’s Sons, New York. 1995.

Stewart, Elinore Pruitt. Letters of a Woman Homesteader. Hougherton Mifflin, Boston, 1913.

Stiles, T.J. Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America. Alfred Knopf, New York, 2015.

•Stratton, Joanna L. Pioneer Women: Voices from the Kansas Frontier. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1981.

Viola, Herman J. Diplomats in Buckskins: A History of Indian Delegations in Washington City. Rivilo, Bluffton, South Carolina. 1995.

The Western Magazine, May 1880. The Western Magazine Co, Chicago.

Reports of Committees: 30th Congress, 1st Session – 48th Congress, 2nd Session, Volume 7. United States, 1880.

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the years 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882, 1883, 1884, by United States Office of Indian Affairs.

Cheyennes In Court, English Westerners Brand Book, v.4, 1962.

Newspapers (all via Newspapers.com)

Leavenworth Times, Leavenworth Kansas

The Daily Commonwealth, Topeka, Kansas

Lawrence Daily Journal, Lawrence, Kansas

The Aitchison Daily Champion, Aitchison, Kansas

The Kansas Daily Tribune, Lawrence, Kansas

The Saline Daily Journal, Saline, Kansas

The New York Times, New York, New York

The New York Tribune, New York, New York

The Chicago Daily Tribune, Chicago Illinois

National Republican, Washington DC

Evening Star, Washington DC

Websites

Kansas State Historical Society

Center for Great Plains Studies

Find a Grave

Oklahoma Historical Society

Legends of Kansas

Kansas GenWeb Project

Library of Congress

Pinterest

Circus History

Plus, all the links I have scattered throughout the text here in the epilogue.

Thanks for reading this series! I hope you got as much out of it as I did. Now, on to the next story. I just have to figure out what I want to write about next!

© Julie Dirkes Phelps; Photographer, Author, Researcher, Archivist, and Storyteller. © Copyright 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, reposting, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without prior written permission. Be cool, don’t plagiarize. If you want to use something, just ask me. I try to make sure to attribute all images to the appropriate sources, but sometimes I inadvertently post an image from an incorrect source (or the image is incorrectly cited from my source), get images mixed up, or accidentally leave something out. Please email me at itsabeautifultree@yahoo.com with any corrections or concerns. Thanks.

This is the dorkiest comment you’re ever likely to get on your blog, but it’s true: I just got out of my chair and gave you a standing ovation. Like real, actual audible clapping and everything. My God, Julie … even your afterthoughts and asides are riveting! BRAVO. You’ve told this story beautifully — every single part of it. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!!! I had to include my afterthoughts because not including my thoughts was killing me. And even my afterthoughts have afterthoughts! I love that you stood and clapped— when I read the ending the first time, I screamed WHAT THE F? at my computer screen and then ordered three books and had them overnighted so I could read them right away! And I write in books while I read, so I had to buy them. It took everything I had not to comment while I wrote! This was such a complicated story— THANK YOU SO MUCH for reading it all!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my gosh … no need to thank me, Julie. Once I read your first two posts I was COMPELLED to stick with you to the end. (Though I admit I’m still reeling from the end. WTF?????!!!!!!! Just … wow.)

PS: I forgot to comment on how much I loved your overhead selfie in the epilogue. I’d like to imagine that this is how you looked to “Wild Hog et al” when they gazed down from the Great Beyond and saw you writing their story. xoxo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha!!!! The end really IS one giant WTF! I just kept wanting to go all Kathy Bates in Misery on that toad Sutton. I felt bad about his kid and all because that really sucks, but knocking up your girlfriend, going on your honeymoon, and partying with your budding while all these guys are rotting in jail was crappy. It was SO obvious that he had no intention of showing up, and he didn’t even have the courtesy to give anyone a heads up.

I will say, though, that Mohler is my new hero, and the phrase “jack legged pettyfogger” is probably my favorite new phrase. So much awesome. Jack legged pettyfogger!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jack legged pettyfogger. Hmm. That does have a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? “I don’t care one Jack legged pettyfogger WHERE Waldo is … I just want him to give back my striped hat!” Thank you for that, Julie! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

That Waldo is a jack legged pettyfogger! I think someone actually used the term in a newspaper too! I need to find it and screen shot it. It’s CLASSIC!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi. I see you read Dog Soldier Justice, the sad story about Susanna Alderdice. I write today, the very day her only son to survive, 4 year old Willis Daily, died in 1920 at the young age of 55. I am curious how DJS impressed you, positive or negative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jeff,

I want to thank you for reading my blog and for commenting. It’s rare that the author of one of my sources contacts me to ask about my experience with one of their works. As for DJS, I have to tell you this: with the shelf of books I collected during the process of researching this piece, there were only a few that I actually read from cover to cover and paid “full price” (meaning Amazon price) and paid expedited shipping for. DJS was one of them. I not only read it cover to cover, but I had a hard time putting it down. It was riveting.

I went at this book from a somewhat unique perspective. Although the Indian Raids and the Dog Soldiers were at the forefront of my mind for this piece, they were only peripheral to my story about the Starrett family in Kansas. The more I researched, the more in-depth I got into the entire Cheyenne experience and had to keep reminding myself why I was reading these books. But this one, I couldn’t put down. It was purely by accident that I even started researching them at all– I initially only wanted to know why there were six Sioux Indian Chiefs in the jail yard in Lawrence!

I had a HUGE range of emotions throughout this book and throughout this piece. My sympathies and my anger hopped the fence so many times that I didn’t know whether I was coming or going half the time. I think the thing that stuck with me most was how much the WOMEN suffered, and how much history has marginalized them and their struggles and their suffering so much. In this case, both the native and the settler women’s stories and histories were swept aside. I mean, really. Who wants to talk about rape and kidnapping and misery? Overall, your book just made me incredibly SAD (for obvious reasons).

I think telling these stories is important. People seem to want to have a hero and a villain. In history, they want a clear-cut good guy and a clear-cut bad guy. I think your book does a good job of showing that there wasn’t either. Both sides did equally horrible things and both sides have done their best to cover up and hide the ugliness they did. Who started it, who did what, and who did it worse really doesn’t matter. As my mom always says, “two wrongs don’t make a right.” Everyone did really bad things, and over a century later, no one is taking responsibility for any of it. The only clear-cut innocents in it all were the women and the children. Especially the women.

When I started reading DJS, I’d just finished reading George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes, and I came away feeling nothing but sympathy for the Cheyenne. But as I read DSJ, I grew SO ANGRY at how Grinnell glossed over any hint of any wrongdoing in his book. It made me feel physically sick at how women were referred to as “spoils of war” and were used as bargaining chips. As I read DJS, I kept flipping back to Grinnell and matching up dates. I just got sadder and sadder and the sick feeling in the pit of my stomach intensified with every paragraph. I should post a picture of my notes in my copy of The Fighting Cheyenne. They aren’t notes to that text. Rather, they are notes to DSJ that I wrote in the margins of TFC. I think my pen ran out of ink.

Willis sounds like he was a truly amazing man who chose to put everything behind him and live his best life rather than dwell on the past or seek revenge or excessive financial compensation or fame from his ordeal. Perhaps that was the only way to get through it. Heartbreaking.

As I read your book, I kept thinking that during the time Susanna was being held, my family (the Starretts) were living in Kansas and raising their family there. Helen and William were well-educated, and both worked for one of the newspapers in Lawrence. Undoubtedly, they were aware of (at least some of) what was happening, and since they lived on the outskirts of town, I’m sure there was some fear in them that this type of thing could happen to them. I can’t imagine the fear any of them may have had.

I live in Williamson County, Texas, and I have stood in the middle of Fort Parker, about an hour or so from here. For whatever reason, we were the only ones there that afternoon, and while my husband and kids explored the fort, I stood in the middle of the grounds and I closed my eyes. I tried to imagine how it must’ve felt to be helpless on the land during a raid. It was horrifying, even though it was 2015 and I knew I was totally safe. But the feeling of sadness was overwhelming.

Your book left an impression on me, and I only wish that there were more accounts like this. Thanks to your book, I know who Susanna Alderdice was. Although the Indian Raids aren’t the focus of my research, they did contribute to the time and place that made up a portion of my great great grandmother’s life. I hope that if (I mean WHEN!) I can publish a book on her life, it will impact someone else the way your book impacted me.

Julie

LikeLike