When I look up into the towering oaks in my yard here in Central Texas, I see tall, beautiful trees, with voluminous branches, vibrantly green with new growth from these crazy spring rains we’ve been getting this year. Their expansive limbs are growing taller and fuller every year, and we’ve watched as they’ve shot up above the roofline of our house—the house we built in this specific spot because of the oak trees. As a family, we’ve enjoyed the shade they’ve provided us on the hot Texas summer days. We love listening to the breeze blow through their leaves, and it’s hysterically entertaining to watch the cats press their noses against the windows and chatter at the birds as they build their nests high up in the branches. I’ve never thought my trees were anything but perfect and beautiful.

And then one afternoon, some guy with a business card and a tree embroidered on his shirt came knocking on my door, wanting to give me an estimate to prune my awesome, perfect, green trees. He told me that they’re filled with mistletoe and that if I continue to neglect them, the semi-parasitic plants will suffocate and kill my beloved trees. He went on to say that it’ll cost me five hundred bucks to rid them of the “garbage” and make them healthy again.

Hold up. What? Mistletoe? Like Christmas? In my oak trees? This guy was talking crazy, so I kindly took his card and told him thanks but no thanks and that I needed to talk to my husband and blah blah blah. A few days later, a different guy with a different business card and a different tree embroidered tree on his shirt came knocking on my door with a similar spiel, only this dude wanted to charge me a grand. A thousand dollars to trim my trees. Then it happened again a few months later. And again a few months later. And it still happens. All. The. Time.

What? The? Heck? Mistletoe? Mistletoe is murdering my trees? Who ever heard of murderous mistletoe? Mistletoe is for kissing, not for killing!

So I flipped open my trusty MacBook and clicked over to google, and, what do you know? These guys with their fancy business cards and spiffy embroidered shirts who keep interrupting my daily bon bon eating, writing, and research are right. We have a mistletoe problem. And since I’ve been ignoring their annoying door knocking and sales pitching for so many years, this pesky parasite has been hiding out in my oak trees, making them appear bigger and fuller bushier and fluffier and healthier than they really are. And it’s kinda murdering my beautiful oak trees.

Mistletoe IS murdering my trees!

OK, so, obviously I’m not an arborist and this isn’t an article about oak trees and potentially murderous, semi-parasitic, mistletoe. But, what IS happening in my yard is not unlike what is happening in thousands of family trees online all over the internet. At first glance, so many of our online family trees look full and healthy, with abundant branches filled with names and dates and fascinating stories. But sometimes, upon deeper examination, a lot of those branches are heavily laden with virtual mistletoe, and these semi-parasitic history murderers are silently killing the authenticity of our family trees.

With the rising popularity of family history and genealogy websites, more and more historical MISinformation is spreading throughout cyberspace and attaching itself to unsuspecting family trees much in the same way the real mistletoe has done in my real-life oak trees. Only instead of invasive plants taking root in real trees, misinformation is taking root in family trees, and the misinformation is destroying their historical accuracy. The trees are bigger, but they aren’t healthier. They aren’t correct. It’s one thing to SAY you’re descended from royalty— it’s another thing to actually PROVE it.

It used to be that family stories and genealogies were handed down orally, and that if something was accidentally misrepresented, it was easily verified or debunked by asking grandma or by checking in family bibles or county and church records. But not anymore. All this virtual mistletoe is making so many online family trees look so big and bushy that it’s becoming harder and harder to determine the real ancestors from the typos or accidental assumptions. All the mistletoe really makes the question of “who do you think you are?” even more confusing.

With websites like Ancestry.com, Genealogy.com and FamilySearch.org, we have more information available at our fingertips than we know what to do with. Hundreds of millions of documents. This simple evolution in modern technology, the ease of adding information to a family tree with a click of a button, and the absence of critical thinking have made what was once a laborious task that required long nights in library basements and hundreds of dollars in copy fees into a challenging task that necessitates patience and critical thinking . Most new members to genealogy sites fall into the trap easily. Heck, even some of us who’ve been at it for decades fall into the trap sometimes, and we should know better.

Here’s the scenario: You’re new to a community like ancestry.com. You sign up and enter the information you already know off the top of your head. And then the magic starts happening. Cute little leaves begin dancing on your tree, and you start clicking and adding and clicking and adding—and as more dancing leaves start popping up, the more voraciously you start clicking and adding and clicking and adding and suddenly, you have this gloriously full family tree that’s filled with interesting and famous and infamous ancestors who have fascinating stories. It’s fun. It’s exciting. It’s overwhelming.

But then suddenly, you realize that you’ve got a problem. You made a mistake somewhere, and now you’ve got second wives who’ve magically become daughters and second cousins who‘ve transformed into brothers— and then you have this other dude who doesn’t even belong here at all. But, but, but…. But the dancing leaf told you this was where he belonged, and five other “cousins” clicked and added him, so it must be true, right? Before you know it, you’ve got a family tree filled with so much virtual mistletoe that you’re either stuck having to weed through every single ancestor and relation to correct the mistakes and relationships (which is a chore in itself) or pay someone with a fancy business card and a spiffy embroidered shirt to clean up the mess you’ve been unknowingly nurturing. Or, you can just start over. No matter what you do, it’s never as much fun as it was the first time.

Don’t feel bad. It happens to everyone—even those of us who should know better (um, Guilty, Party of One my table is ready!). But, if you’re responsible with your research and critical in your thinking, you can keep this virtual mistletoe from taking hold in your family tree before you need help (or an all-nighter) to clean it up.

But what if it’s not your fault?

It’s a rare thing, but sometimes mistletoe comes from seemingly credible published sources. What happens then?

Here’s something that happened to me: A few months ago, I found a mistake that was published over a hundred years ago, and at first, I was really excited at the cool new discovery. I thought I’d found a fantastic hint that might help me break through a substantial brick wall. But before I ran with it, I decided to look at the information from various angles to see if it checked out. Something about it just didn’t seem right. Upon further scrutinization, I found that there was no truth to the factoid, and there’s no explanation as to how or why it appeared in print in the first place. It seems as though the author had done the 19th century version of clicking and adding a dancing leaf without properly verifying his facts.

In 1881, James Brown Scouller published A Manual of the United Presbyterian Church of North America, 1751-1881. In his 648-page book, Scouller composed a condensed history of the Presbyterian Church in the United States and included chapters on the various Presbyteries and Synods (which I found interesting and informative because I didn’t know much about Presbyterians before reading it). He also included a short snippet about each Presbyterian congregation, ministry, seminary, college, and periodical in the country. Then, J.B.S. crafted a brief biography of every single minister ever ordained in the history of every single Presbyterian Church in the entire United States of America for a one hundred and thirty year timespan. That’s a LOT of ministers. So, understandably, mistakes were inevitable, and he said as much in his preface.

On page 279, J.B.S. composed the following biographical sketch of my 3x great grandfather, Dr John Ekin, D.D.:

The tiny detail that piqued my interest was this one sentence fragment:

First of all, Rev John Ekin, D.D. never worked in the United States Quartermasters Department. Secondly, he didn’t have a brother named James. He two brothers, but neither of them were named James. And he didn’t have an uncle or a first cousin named James either.

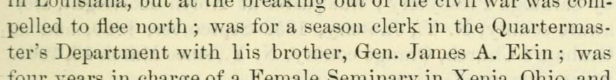

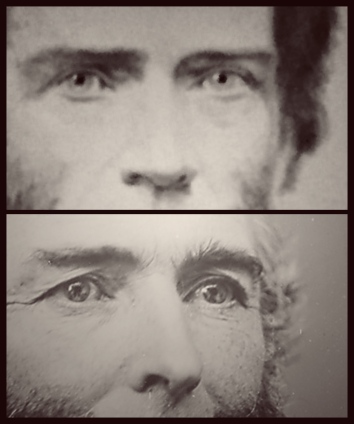

Now, there was a Brevet Brigadier General James Adams Ekin who was close enough to Rev John Ekin’s age that the two men could have been brothers— James Ekin was only four years younger than John. But they weren’t brothers. I can’t even find evidence that they were even related as close second cousins. Both men have extended roots in County Tyrone, Ireland, but I wasn’t able to find anyone directly linking them together. The only thing that may have drawn Scouller to his assumption was the fact that Gen Ekin’s name was in the news a lot during the time he was compiling his information. Well, that and the two men were both active in the Presbyterian Church, both men were tall, slender, and handsome, and both had strikingly hypnotic gorgeous blue eyes.

Like John Ekin, James Ekin was born in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area. John was born in 1812; James was born in 1819. John went into the ministry where he served as an influential pastor in the Allegheny, Pennsylvania area before accepting a call from the Red River Presbytery in the warmer climates Louisiana, a location more beneficial to his health at the time. His not-brother James went into the steamship building business in the Pittsburgh area. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Rev John Ekin D.D. sent for his daughters who had accepted teaching positions in other locations, and the entire family returned to the north and opened a seminary for girls in Xenia, Ohio. James Ekin joined the Pennsylvania Infantry and quickly rose through the ranks in the Army and was noted for his excellence in the Quartermaster’s Department. But, it wasn’t his quartermastering that made him famous-ish.

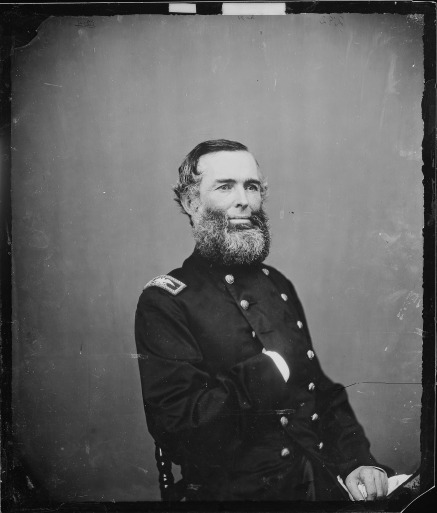

During James Adams Ekin’s military service, he attracted the attention of high ranking government officials, including that of President Abraham Lincoln. Following Lincoln’s assassination by John Willkes Booth, Brevet Brigadier General James A. Ekin was detailed as a member of the Honor Guard who accompanied the President’s remains on the train procession from Washington D.C. to Springfield, Illinois.

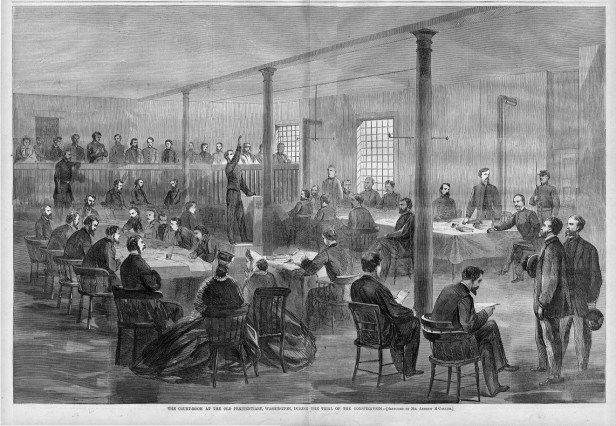

Shortly after Lincoln’s burial, President Andrew Johnson formed a commission of high-ranking military officers to preside over the trial of Booth’s accused conspirators. General James Ekin was among those appointed to this historic military tribunal. Given his kind and gentle nature, Ekin was an unlikely choice for the court, and was said to have been less than thrilled with his appointment to it. Among those on trial for the assassination of the President was Mary E. Surratt.

The tribunal heard testimonies from over 350 witnesses for nearly two months during May and June of 1865. Although the commissioners were confident Mrs Surratt’s guilt, they were less confident in sentencing a woman to death. After initially falling short of the required majority needed to secure her execution, the tribunal reached a compromise. They found her guilty on all but two of the charges and sentenced her to the scaffold, but five of the nine judges immediately appealed to President Johnson for clemency, and the petition was attached to the order of execution. General Ekin penned the letter and it was signed by David O. Hunter, August V. Lautz, Robert S. Foster, James A. Ekin, and Charles H. Tompkins (Lew Wallace, Thomas M. Harris, David R. Clendenin, and Albion P. Howe did not sign it).

Five days later, the order for execution and the petition for clemency were delivered to the President. He signed the execution order, but not the petition for clemency. On July 7, 1865, Mary E. Surratt became the first woman executed by the United States government. The historic military tribunal and execution were controversial, and had the trial taken place months later, the outcome undoubtedly would’ve been much different.

Throughout the trial and during its aftermath, General Ekin’s name was published in the newspapers as a part of the tribunal. And his name has gone down in history as a member of the committee. If you pay close enough attention to the 2010 film, The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford, you’ll hear his name. (General Ekin was played by actor John Deifer, but the role was small enough that he wasn’t credited, and there’s no picture of the actor on IMDB.)

Back to mischievous mistletoe in the trees. Like his not-brother John, General James Ekin was a well-respected and high-ranking member of the Associated Reformed Church, and later, the United Presbyterian Church. Both Ekin men were compassionate, smart, tall, kind, well-spoken, well-educated, well-respected, and loved by their communities.

But, they weren’t brothers. And there’s no evidence that they ever worked together. They could have have met each other since they were both Presbyterians and they were both from the same part of Pennsylvania and they both moved around the country a lot. Could have. If they did meet, it’s possible that they could have maybe joked that they were brothers, but if they did, it was nothing more than playful banter. And the “season” that John would’ve worked in the Quartermaster’s Department…. well, it just doesn’t fit into John’s timeline anywhere. Although there aren’t many pictures of Rev John Ekin, D.D., his whereabouts are pretty well documented throughout his later life.

Despite the fact that this tidbit of information isn’t true, I still see it on family trees all over the internet. But it’s nothing more than mischievous mistletoe.

Yet like the mistletoe, it didn’t take more than a few minutes—and nothing more powerful or more expensive than a simple google search—to figure out that the “extra foliage” didn’t belong there. Just for good measure, I even messaged one of James’ descendants to see if she knew of any connection between the two men (I found her on Find a Grave). And, just like getting a second estimate from an arborist, she confirmed my suspicions. That’s why James Adams Ekin’s dancing leaf isn’t on my family tree, even though I really wanted him to be there.

But, regardless of the evidence, I still get hints to add him to my tree because other people continue to blindly click and add. So I keep on clicking “ignore,” and I keep hoping that John’s descendants will think twice when they see that he’s not on my tree and they’ll stop and investigate before adding him to theirs. Not because he’s not an awesome historical figure, but because he’s not John’s brother.

But, regardless of the evidence, I still get hints to add him to my tree because other people continue to blindly click and add. So I keep on clicking “ignore,” and I keep hoping that John’s descendants will think twice when they see that he’s not on my tree and they’ll stop and investigate before adding him to theirs. Not because he’s not an awesome historical figure, but because he’s not John’s brother.

In the end, isn’t it better to have a smaller, more historically accurate family tree than a big and flashy tree filled with mistakes? And, unlike the trees out in the yard, you can use Google or Wikipedia and other websites (and a few minutes of critical thinking) to prune out the virtual mistletoe so it won’t kill the historical integrity of your family tree—and, unlike rely life mistletoe, it won’t cost you a thousand dollars to fix.

Now I have to decide which guy to call back to get this mischievous, murderous mistletoe out of my real oak trees.

© Julie Dirkes Phelps; Photographer, Author, Researcher, Archivist, and Storyteller. © Copyright 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, reposting, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without prior written permission. Be cool, don’t plagiarize. If you want to use something, just ask me. I try to make sure to attribute all images to the appropriate sources, but sometimes I get mixed up or inadvertently leave something out. Please contact me with any corrections or concerns. Thanks.

Images by the author except for the historical images of James Ekin and of the Military Tribunal. Those I found on Wikipedia and have been published in numerous places. They are in the public domain and are available in the National Archives.

Who knew that mistletoe could be such a problem — or that it could invade family trees? Thank you for another captivating (and informative) post. You may have saved many a soul from genealogical frustration with this post, by reminding us that just because the paper is yellow and the esses look like effs doesn’t make it so. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had no idea either! And with all the mistletoe all over the internet…. If I can save ONE FAMILY TREE from infection, I will be happy! Ha! Sadly, I think the worst perpetrators are content with simply adding someone semi-famous to their family than in actual historical accuracy. Sad. And the esses and effs…. Oh my. Early newspapers swap them all the time. It’s like they had some bizarre speech impediment. Funny to jokingly READ words with effs instead of esses!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Adding fomeone femi-famouf to your family tree to make yourfelf feem more important. Can you imagine? Fheefh! It remindf me of thofe royal familief of yore who claimed to be defcended from Greek godf and fuch. Af if it’f not enough of a miracle to fimply be ALIVE! Well, you’ve certainly done your part to help prevent “miftletoe contagion.” Hatf off to you for that. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha!!!! I once found a family tree where fomeone went all the way back to Adam & Eve and GOD. Hmmmmmm…. Miftletoe? I think fo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

People are such nutballs! And I presume they claim to have some photos of God among their heirlooms? 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, right? I just kept reading and shaking my head. It was very entertaining.

LikeLike

I’ve been clicking on leaves and looking at other’s trees and have found so many copy errors. I want more information on a few of my ancestors, but I won’t link the incorrect data to my tree. Kids born before parents, families living in two states at the same time, sooo frustrating!

Love your essay!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are so many errors, but so much good information too. All you can do is verify your own information and make sure that your own tree has no mistletoe in it! When/if I have the opportunity to let someone know they have an error, I try to do it nicely, but mostly, people just ignore well-meaning suggestions because they want lots of leaves or high profile ancestors.

Thank you so much for your comment!

LikeLike

Hi Julie,

I’m a descendant of the James A. Ekin Family. He did not have a brother according to our family records, just one sister – Elizabeth Ann Ekin Love of Pittsburgh . Who did you talk to from Find-a-Grave? I’d be interested in finding another family member. Yes, we are very proud of General Ekin!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi!!! I’ve pretty much ruled out the probability of your Ekin and my Ekin being brothers, but they may be more distantly related (perhaps more like cousins or second cousins maybe?). I’ve connected with some of my Ekin family and we spent a weekend together. We were all third and fourth cousins, never met before, and after about 15 or 20 minutes, it was almost like we’d spent our whole lives growing up together. It was awesome. I need to get back to blogging, but I’ve been so distracted! Maybe we’ll find an Ekin connection somewhere between us! That would be FUN! -Julie

LikeLike

Julie

Like yourself I thought Rev John Ekin was related to James Adams Ekin but as a result of YDNA testing they are definitely not related at all, James Adams Ekin father was from Ruskey near Coagh County Tyrone near Magherafelt The Rev John Ekin family might have been from County Antrim this is not confirmed

Brian Eakin a Y700 DNA relation of James Adams Ekin

LikeLiked by 1 person